Exercises required for marine transition

A series of drills and exercises, including one large no-notice drill, helped assess the new system in Prince William Sound.

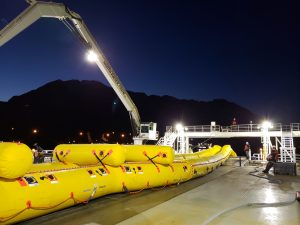

Throughout the past year, Alyeska conducted a series of exercises designed to meet requirements from the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation and train the crews aboard Edison Chouest Offshore’s new vessels. Some exercises were conducted during windy conditions and others during darkness.

In June, the department approved major amendments to the oil spill contingency plans for the Valdez Marine Terminal and the tankers that transport oil through Prince William Sound. These amendments stemmed from the change of spill prevention and response contractors to Edison Chouest Offshore, who took over from Crowley Maritime last July. The approval came with conditions, which required specific exercises and training for the new equipment and personnel.

The department required each of the five escort tugs, the four general purpose tugs, and the Ross Chouest utility tug to conduct exercises with oil spill response barges. In addition, the department specified that some of these exercises had to occur in winds of at least 20 knots (23 miles per hour) and in darkness.