A new study hints that the herring population in Prince William Sound could be on the rise.

In the early 1990s, the numbers of herring declined drastically, destroying a healthy fishery. The reason for that crash has never been confirmed, though the Exxon Valdez oil spill is considered a contributing factor.

Since then, the herring population has never recovered to the point that fisheries could permanently reopen. Then in 2015, the population crashed again, possibly due to a disease outbreak.

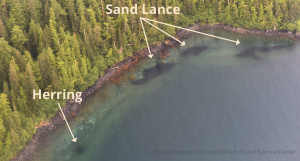

Researchers at the Prince William Sound Science Center have been studying herring for several decades to find out why the population is struggling to recover. The author of the report, Dr. Scott Pegau, coordinates the center’s herring research and monitoring programs. Part of his work includes surveying the coastline of Prince William Sound from a small plane to count the size, numbers, and age of schools of juvenile herring.

The Council sponsored the last four years of these surveys. Forage fish species, such as herring, are often found in shallow coastal waters, so they are particularly susceptible to the effects of an oil spill. The data on where schools of herring and other “forage fish” tend to congregate could be used to help protect those areas in case of a spill.

Second year of increased numbers of herring

The different species have different characteristics, for instance, herring form circular or oval-shaped schools, while sand lance schools are irregular.

The age of the fish can be identified from the air too. Schools of young herring sparkle as light reflects from the fish as they roll. Older herring have larger, more distinct flashes.

The populations of forage fish can fluctuate, so it’s important to be able to compare the numbers and sizes of schools to past years. Similar surveys have been conducted as far back as the 1990s.

The number of schools of 1-year-old herring is used to estimate future population growth. Surveys conducted in 2022 found an increase in these young herring for the second year in a row. The researchers are hopeful that this means an increase in the number of herring that will return to spawn in the next two years.

“If this is true, we can expect that the herring population will have robust growth in the near future,” Dr. Pegau notes in the report.

Dr. Pegau also advises caution. He notes that these surveys were conducted during a period of unusually warm and sunny weather, and that this could have inflated the count. Future surveys will confirm whether this increase will be permanent.

Read more about the Prince William Sound Science Center’s herring research on their website: Prince William Sound Science Center’s Herring Research and Monitoring Program