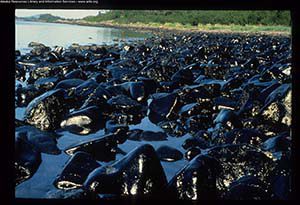

New techniques in the field of genetic analysis are improving our understanding of the effects of oil spills.

Since 1993, the Council has gathered data on the presence of hydrocarbons in sediments and blue mussels in the region. Samples of sediments and mussels are collected and analyzed for the presence of oil or other pollutants that originate from the Valdez Marine Terminal and tankers that ship oil from there.

In 2019, the Council began looking at new methods to measure the impacts of oil on the environment. In April 2020, a spill from the terminal leaked approximately 1,400 gallons of oil into Port Valdez. This unfortunate incident presented a unique opportunity to learn.

The new research analyzes the genes of blue mussels using a technique known as “transcriptomics.” Transcriptomics involves measuring how particular genes are expressed in an organism. This expression can be affected by conditions in the environment.

The research began in 2019 with a pilot study. The early research looked at 14 specific genes. More recent work expanded the study to over 7,000 genes, and is summarized in a new report sponsored by the Council.

The researchers compared samples of mussels taken from sites near the terminal, near the Valdez harbor, and a third control site. They found some interesting results.

Effects of oil on genes lingers

After the April 2020 spill, the levels of oil in the mussels had declined by August, however the mussel’s genes showed evidence of lingering effects.

Different pollutants have different effects

More recently, researchers tried to identify how the effects differed according to different contaminants. The crude oil-contaminated samples were compared to samples from the Valdez harbor, which were contaminated with pollutants such as diesel fuel or vessel exhaust, and the control site.

Genes such as those associated with stress, neurotransmitters, and the immune system were among those that varied between the three sites.

Results expected to have far-reaching implications

The information in these studies will help improve the Council’s monitoring program in the future. The researchers noted in the report that the findings are not just applicable to Alaska but could potentially improve monitoring in marine environments around the world.