In 1989, when a young Patience Andersen Faulkner was working as a legal aide in the picturesque town of Cordova, disaster struck when crude oil spilled into Prince William Sound from the tanker Exxon Valdez.

Part of her job was to listen to the folks who came into the law office talk about their experiences with the spill.

“They would tell me how things devastated them emotionally,” she says. Even though the spill affected her too, she just listened.

The town didn’t have much in the way of mental health services, so Andersen Faulkner pushed the lawyers she worked for to get the community some help. They introduced her to Dr. Steve Picou, a sociology professor at the University of South Alabama.

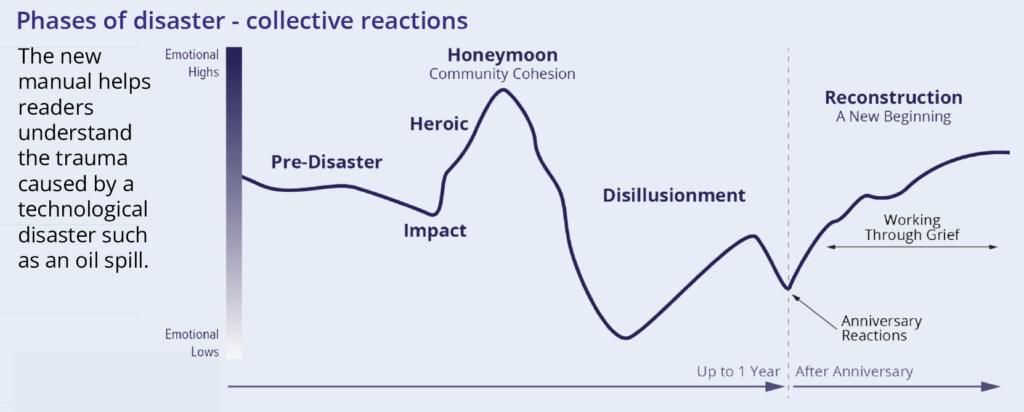

Dr. Picou had been studying the impacts that technological disasters had on communities. While the effects of natural disasters were well-understood, technological disasters were a relatively new field, with little documentation. After the spill, he came to Alaska to study how the disaster affected the community of Cordova. This work developed into the Council’s guidebook called “Coping With Technological Disasters,” designed to help communities cope better with similar disasters in the future.

A technological disaster is human-caused. These accidents are caused by the failure of systems that are in the control of people.

Examples include an oil spill, train derailment, plant explosion, or other accident, which have different effects on communities than a natural disaster.

How different types of disasters create different social environments

Not only are the effects of a technological disaster long-lasting, they differ from other types of disasters. After natural disasters, such as earthquakes or typhoons, there are systems in place for support, such as government agencies. Communities often bond during efforts to rebuild.

Following a technological disaster, there are questions about responsibility, victim-blaming occurs, and complex lawsuits are common. All of these can cause lingering psychological damage.

In 2006, Dr. Picou surveyed Cordovans to examine the long-term effects of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. His work showed that 17 years after the spill, recovery was progressing, but psychological stress from the spill was still present.

Some natural disasters can have elements in common with technological disasters. Problems with preparation and response, such as occurred after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, can cause similar community effects.

Learning to listen

Andersen Faulkner noticed that when the clients talked through their problems, they often left feeling better.

“They weren’t cured of anything, they didn’t have any money, but they at least knew they had a tool within themselves on which to draw,” she says about the experience at the time.

The Council’s 1996 guidebook by Dr. Picou included a section on training community members to become peer listeners. This work was based on the experiences of Andersen Faulkner and other Cordovans. In 1998, Andersen Faulkner joined the Council’s Board of Directors, where she served as a representative of the Cordova District Fishermen United until 2022. She helped guide the development of updates to the guide and manual.

Over the years, this program was used and adapted for recovery following disasters such as Hurricane Katrina, the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, the Council updated the “Coping With Technological Disasters” Guidebook. This year, the Council sponsored a major overhaul of the peer listener program. A newly revised Peer Listener manual incorporates many advances in the fields of peer-to-peer support and community resilience.

How the new manual can help

The revised manual is designed to assist communities that have been through a disaster. Here are a few ways the manual can be beneficial.

For individuals:

- Skills to be a better listener

- Examples of supportive and reassuring responses

- Warning signs that additional help is needed beyond peer support

- How to recognize when you are getting overwhelmed and need to take care of yourself

- Links to resources for additional help, including many specifically for Alaskans

For communities:

- Promotes a network of support that increases resiliency

- Fosters empathy among community members

- Identifies vulnerable populations

Download the new manual: Peer Listener Training Manual