Systems and Methods: Connecting across the Exxon Valdez oil spill region

Science Night is an annual event hosted by the Prince William Regional Citizens Advisory Council. Topics focus on research related to the safe transportation of oil through Prince William Sound.

Individual presentations can be viewed below, or you can view the full playlist directly on the Council’s Youtube Channel: Science Night 2023

On this page:

- Let the Hydrocarbons in Prince William Sound Talk

- Forage Fish Update

- Tsumani/landslide hazards in Prince William Sound

- Alaska Spill Response Wildlife Aid

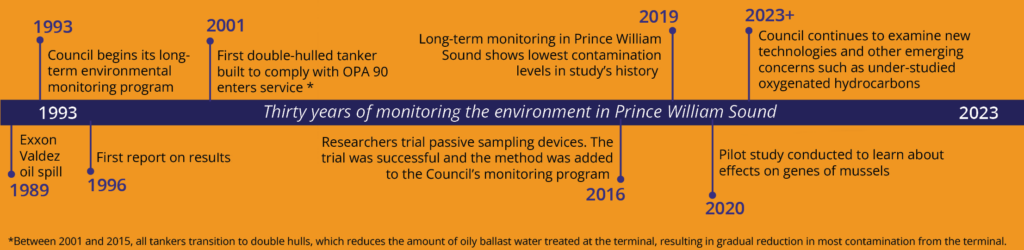

Let the Hydrocarbons in Prince William Sound Talk: 30 years of Environmental Monitoring through PWSRCAC’s LTEMP

Presenter: Dr. Morgan Bender, Senior Scientist, Owl Ridge Natural Resource Consultants, Inc.

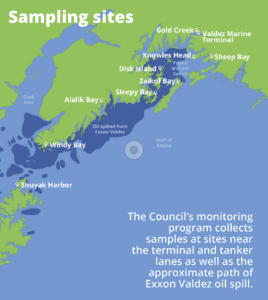

The PWSRCAC’s Long-Term Environmental Monitoring Program (LTEMP) is one of the longest-standing hydrocarbon assessment programs of its kind and provides us with annual data on how and where hydrocarbons enter Prince William Sound and the potential effects they may have on the marine ecosystem. Morgan, an Alaska-based ecotoxicologist, will lead us through the 30-year LTEMP investigative process and major findings to inform and excite Science Night participants on LTEMP’s past, present, and future.

View Let the Hydrocarbons in Prince William Sound Talk directly on YouTube.

Forage Fish Update

Presenter: Scott Pegau, Research Program Manager, Oil Spill Recovery Institute

Forage fish provide a critical link between plankton and large predators like birds, mammals, and other fish. Pacific herring, sand lance, capelin, and juvenile pollock are a few of the many forage fish in PWS. Most of the information we have on forage fish is associated with herring because of its historic commercial importance but there is some information on other species. This presentation takes a look at some of the existing research into forage fish in Prince William Sound.

View Forage Fish Update directly on YouTube.

Advancing our understanding of tsunamigenic landslide hazards in Prince William Sound, Alaska

Presenter: Dennis M. Staley, Research Physical Scientist, U.S. Geological Survey – Alaska Volcano Observatory

Exposure to landslide and tsunami hazards are a part of life for those who reside in the seaside communities of coastal Alaska and the people who work or recreate in coastal waterways. Recently, the recognition of the landslide-generated tsunami hazard posed by the Barry Arm landslide in northwestern Prince William Sound has attracted considerable attention in the public and media, at local, state, and federal governments, and in the scientific community. This presentation focuses on the ongoing effort to assess hazard and warn for a tsunami produced by the Barry Arm landslide, and on scientific investigations into the prevalence of this type of natural hazard at other locations in Prince William Sound.

View Advancing our understanding of tsunamigenic landslide hazards in Prince William Sound directly on YouTube.

Alaska Spill Response Wildlife Aid

Presenter: Bridget Crokus, Deputy Oil Spill Response Coordinator, USFWS Alaska Region

Protecting fish, wildlife, and their habitats is a primary response objective after an oil spill. First-hand accounts of wildlife in or near an oil spill are invaluable to a successful wildlife response. Bridget will present the Alaska Spill Response Wildlife ID Aid, a tool developed to help spill responders “take a wildlife minute” and record the wildlife they see.

View Alaska Spill Response Wildlife Aid directly on YouTube.